Going Down to the River - Conception and Preparation

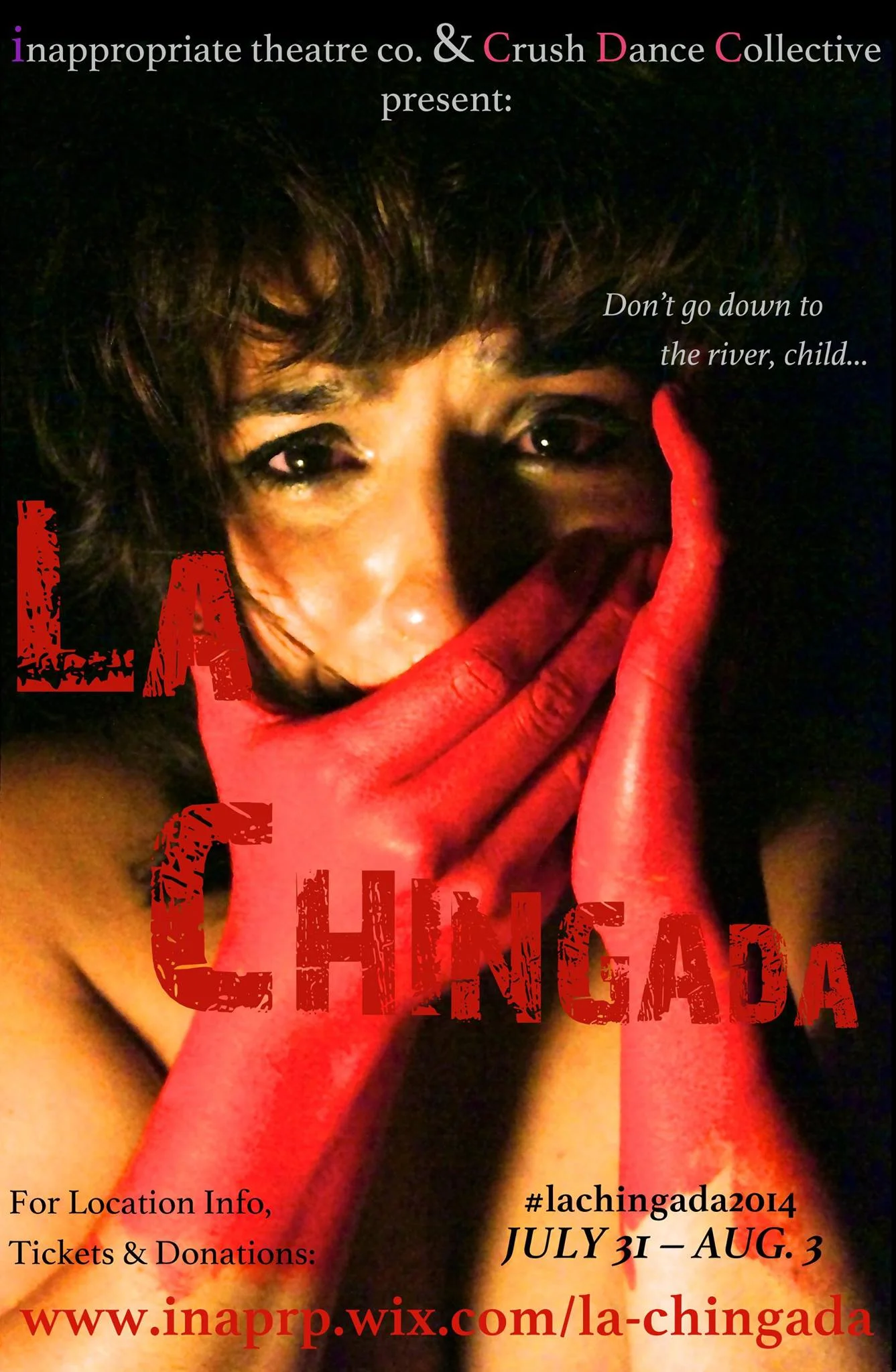

Growing up in South Texas on the border of Mexico, I heard the story of La Llorona all the time. She was more familiar than the boogeyman and more terrifying than the monster under the bed. Everyone’s version of her tale was slightly different, depending on where they grew up, where they heard it first, or what their family had passed down. One thing was always certain, however: She was guilty. Her wet, grieving soul would wail as it wandered the rios, and her screams would haunt our dreams into adulthood. I no longer fear her hands snatching me away or the riverbanks she is said to appear by, but her story has never stopped haunting me. As I have studied literature and theatre and have seen her story in myths and legend from all over the world, I cannot help but wonder why. What is it about this story that makes it worth telling and retelling? Why do we sympathize with Medea, and vilify La Llorona? Why is it a ghost story and not a tragedy, a fable, or a battle cry? What is it about a woman defying societal expectation that terrifies us? Why is it that no matter how many people I asked to tell me their versions, La Llorona never gets to speak? A whole life of love and loss, and she is reduced to three words, “Ay, mis hijos!”

Legends do not get to tell their own stories, so if we gave the voiceless woman a chance to set the story straight... What would she teach us?

Gathering Materials

Assembling the text was one of the most enjoyable parts of the pre-production. In the manner of programmed oral interpretation, I stitched together language, images and circumstances to create a coherent story line.

Given the nature of the story and the way I wanted to unravel it, I decided to utilize found text and devised movement for the piece. I read dissertation papers, poetry, short stories, ghost sightings, plays, and feminist interpretations of Chicano literature. With the rich text of Euripides juxtaposed against the heartbeat of slam poetry, the script quickly found a voice that transcended time and place; it was both ancient and familiar, somber and kinetic. As I gathered versions of the tale, I could not escape the way her story (and the stories of all Chicano women) was deeply intertwined with those of La Virgen de Guadalupe (the Virgin Mary), and La Malinche (the mother of the mestizos, or mixed/Mexicanpeople). These three feminine icons slowly became the pillars of the piece. A holy trinity, if you will. Deity, emotional/spiritual entity, and human. Peace, rage, and grief. This led to the addition of liturgical iconography and ritual within the piece. Pairing mysticism and Catholicism with the indigenous sort of witchcraft attributed to Medea added to the piece’s voice. The poetry of Anne Sexton and Walt Whitman, with their carnal and aggressive imagery, became the Lover’s tongue. He was desirable, well spoken, and made no mistake about what kind of man he was. More complex than a cheater or a villain, he evolved into a complex individual capable of making as many mistakes as La Llorona. To counter The Lover’s voice, La Llorona communicated through movement-denied of a voice until the very end. The chorus became the fusion of the two worlds. Speaking both in poetry and movement, they intertwined both stories with the remaining literature and contemporary texts. At times they stood proxy for the audience, other times for the characters -neither of our world nor from hers-observers, participants and perpetuators of myth.